IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY THIS SITE IS NOT MONITORED. FOR CURRENT INFORMATION GO TO HTTPS://EMERGENCY.MARINCOUNTY.GOV.

How Homes Ignite

Buildings ignite as a result of embers, radiant heat, and/or direct flames. Here wildfire scientists Jack Cohen and Steve Quarles explain how wildfire embers ignite homes.

Embers

Embers are the most common cause of home ignition. They are light enough to be blown through the air and can result in the rapid spread of wildfire by spotting (in which embers are blown ahead of the main fire, starting other fires). Should these embers land on or near your house, they could just as easily ignite nearby vegetation, accumulated debris, or enter the home (through openings or vents).

Recent research indicates that two out of every three homes destroyed during the 2007 Witch Creek Fire in San Diego County were ignited either directly or indirectly by wind-dispersed, wildfire-generated, burning, or glowing embers (Maranghides and Mell, 2009), and not from the actual flames of the fire. Watch this simulation of a home ignited by embers to see just how dangerous wind-blown embers can be.

Radiant Heat

Interesting discussion by wildfire scientist Jack Cohen regarding difference and impact between radiant heat and relatively small embers on home ignition.

Near-home ignitions can subject some portion of your house to either a direct flame contact exposure (where the flame actually makes contact) or radiant heat exposure (the heat felt when standing next to a campfire or fireplace). If the fire is close enough to combustible material, or the radiant heat is high enough, an ignition will most likely result. Even if the radiant exposure is not large enough or long enough to result in ignition, it can preheat surfaces thus making them more vulnerable to ignition from a flame contact exposure. With any one of these exposures, if no one is available to extinguish the fire and adequate fuel is available, the initially small fire will grow into a large one.

Direct Flames

One of the misconceptions about home loss during wildfires is that the loss occurs as the main body of the fire passes. Research and on-the-ground observation during wildfires have shown that the main flame front moves through an area in a very short period of time – anywhere from one to ten minutes, depending on the vegetation type (Butler et al., 2003; Ramsay and Rudolph, 2003). Homes do not spontaneously ignite; they are lost as a result of the growth of initially small fires, either in or around the home or building.

The wildfires that are clearly remembered by the general public are those where hundreds of homes are lost. During these events, many homes were lost because the wildfire became an urban fire where the home-to-home spread of fire became more significant than wildland-to-home spread of fire, especially with decreasing separation between homes (Cohen 2008; Institute for Business and Home Safety, 2008).

Ember Accumulation Study

This is a new study which describes areas around the home where embers accumulate during a wildfire. It is often the heat from a group of embers rather than a single ember that causes homes to ignite. Embers tend to accumulate in areas where leaves blown by the wind accumulate. You can easily identify these areas around your home and pay extra attention to maintenance in these areas.

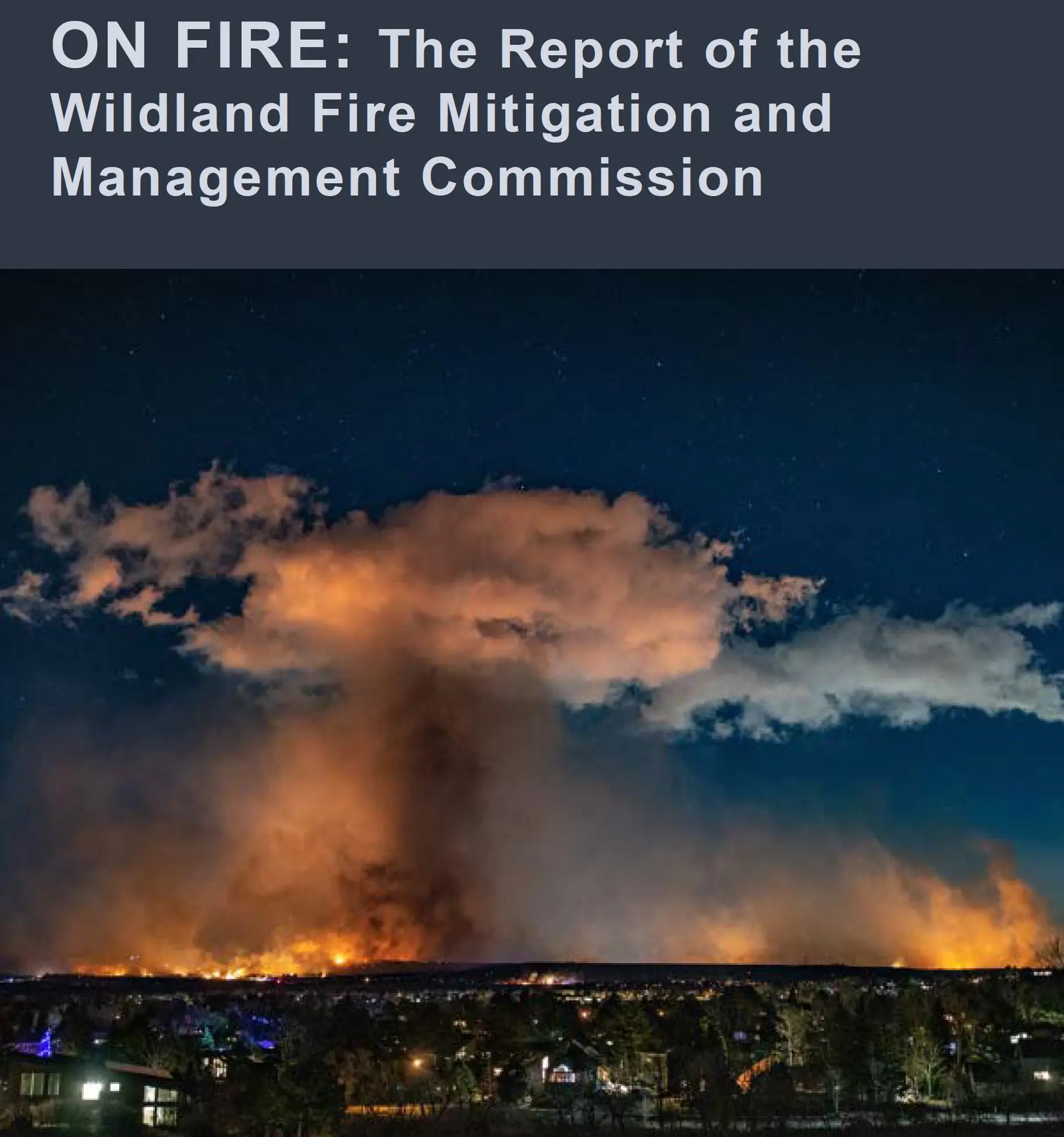

Wildfire Mitigation Commission Report

The wildfire crisis in the United States is urgent, severe, and far reaching. Wildfire is no longer simply a land management problem, nor is it isolated to certain regions or geographies. Across this nation, increasingly destructive wildfires are posing ever-greater threats to human lives, livelihoods, and public safety.

In the face of this national challenge, Congress took bipartisan action to establish the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission and charged the 50-member Commission with the ambitious task of creating policy recommendations to address nearly every facet of the wildfire crisis, including mitigation, management, and post fire rehabilitation and recovery.

The suite of recommendations that follow outline a new approach to wildfire, one that is proactive in nature, better matched to the immense scale and scope of the crisis, and more reflective of the multi-scalar, interrelated nature of the overall system. Importantly, just as there is no single cause of this crisis, there is no single solution.

Among the core themes of the Commission’s recommendations is a call for greater coordination, interoperability, collaboration, and, in some cases, simplification within the wildfire system.

Lahaina: From Conflagration to Resilience

While the unique geography and topography surrounding Lahaina contribute its vulnerability, the data IBHS collected in Maui demonstrates the acute reality of wildfire in a suburban community. This also aligns with IBHS’s scientific research and field observations over the past decade. Observations in Lahaina advance scientific knowledge by demonstrating the factors that are most important for understanding how wildfires enter communities from grasslands and how wildfires spread within communities once the initial structural ignitions occur.

Wildland fire entered Lahaina through connective fuels that bridged the grasslands with the community. These connective fuels are present in many forms, ranging from natural elements like vegetation (e.g., wildland grasslands, shrubs, and trees) to manmade objects such as vehicles and building components like fences. These connective fuels created a pathway for fire to reach and ignite structures—setting off a conflagration.

Once the wildfire entered Lahaina, it spread throughout the community. From observations on the ground, IBHS identified ten community and building features with the greatest impact on how the fire spread within Lahaina— which drives which structures escaped destruction and which ones did not. By a wide margin, structure spacing—the distance between one structure and another—was the most critical factor to fire spread within Lahaina.